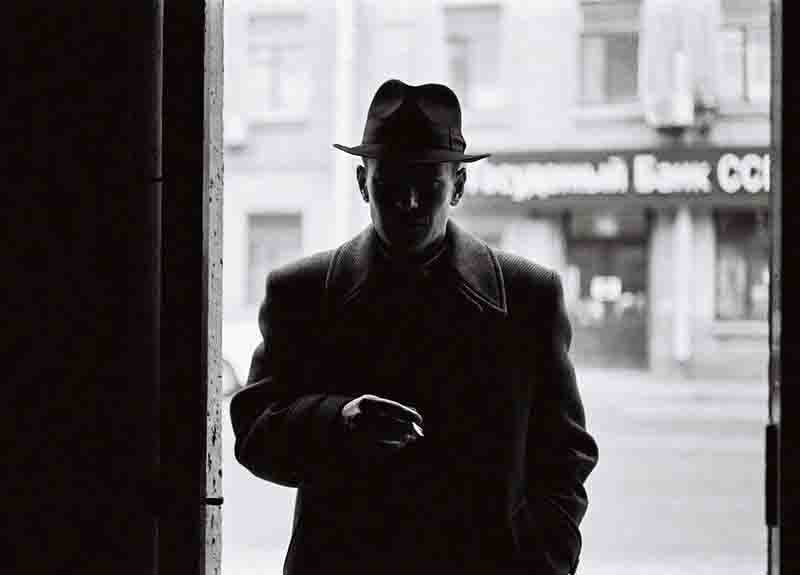

A haunting look at the world of espionage in the Soviet Union. From dead drops to double agents, the shadows of the Cold War tells a story of a global chess match played in the dark.

While American and British scientists raced to build the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, an invisible network of Soviet spies worked in the shadows to steal their secrets. Soviet intelligence successfully penetrated the Manhattan Project, obtaining classified information that would accelerate the Soviet atomic program by years.

The Soviet Union maintained parallel intelligence operations through both the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) and the GRU (military intelligence). These agencies recruited agents from among American and British scientists, many of whom sympathized with the Soviet Union as an ally against Germany.

The extent of Soviet espionage remained largely unknown until the 1990s, when the Venona Project decrypts were declassified and former Soviet archives opened. These revelations confirmed what Cold War critics had long suspected: the Soviet atomic bomb was built not just by Soviet scientists, but by American and British secrets funneled through an elaborate spy network.

Key Concept: ENORMOZ

ENORMOZ was the code name for Soviet intelligence operations targeting the Manhattan Project. The operation involved multiple spy rings, couriers, and handlers working across the United States, Canada, and Britain. The scale of the operation demonstrated the high priority Stalin placed on obtaining atomic secrets.

The Soviet Spy Network

Soviet intelligence began targeting the American atomic program as early as 1942, shortly after the Manhattan Project's formation. The NKVD and GRU established sophisticated networks that gradually penetrated the project's key facilities at Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, and the University of Chicago's Metallurgical Laboratory.

Recruitment Methods

Soviet recruiters targeted scientists and technicians who were politically sympathetic to communism or the Soviet war effort. Many recruits were motivated by ideology, the desire to help the Soviet Union defeat Germany and prevent American monopoly of atomic weapons. Others were motivated by money or blackmail. The recruiters operated through front organizations, communist party cells, and personal contacts.

"The information from our agents in the United States is extremely valuable. It allows us to avoid years of work and millions of rubles in unnecessary research."

Communication Networks

Soviet spies used sophisticated methods to transmit information to Moscow. These included coded radio transmissions, microfilm hidden in everyday objects, dead drops in public locations, and personal couriers. The Soviets employed complex encryption systems that American cryptanalysts struggled to break, until the Venona Project succeeded in decrypting thousands of Soviet messages.

The Venona Breakthrough

The Venona Project, begun in 1943, eventually decrypted thousands of Soviet intelligence messages. These decrypts provided irrefutable evidence of extensive Soviet espionage and identified numerous spies by their code names. However, the project remained secret until 1995, meaning much of the evidence could not be used in contemporary prosecutions.

The Atomic Spies

Several individuals played crucial roles in Soviet atomic espionage. Their motivations varied from ideological commitment to financial gain, but their impact was uniformly significant in accelerating the Soviet nuclear program.

Klaus Fuchs: The Most Valuable Spy

Klaus Fuchs was arguably the most important Soviet spy in the Manhattan Project. A German-born physicist who fled Nazi persecution, Fuchs became a British citizen and worked at the Los Alamos laboratory from 1944 to 1946. As a member of the theoretical physics division, he had access to the most sensitive bomb designs.

Klaus Fuchs

• German-born British physicist

• Worked at Los Alamos 1944-1946

• Provided implosion bomb designs

• Arrested 1950, sentenced 14 years

• Emigrated to East Germany 1959

• German-born British physicist

• Worked at Los Alamos 1944-1946

• Provided implosion bomb designs

• Arrested 1950, sentenced 14 years

• Emigrated to East Germany 1959

Rosenberg Ring

• Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

• David Greenglass (machinist)

• Harry Gold (courier)

• Focused on Los Alamos secrets

• Executed 1953 (Rosenbergs)

• Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

• David Greenglass (machinist)

• Harry Gold (courier)

• Focused on Los Alamos secrets

• Executed 1953 (Rosenbergs)

The Rosenberg Spy Ring

Julius Rosenberg, an electrical engineer, coordinated a network of spies that included his wife Ethel, his brother-in-law David Greenglass, and courier Harry Gold. Greenglass worked as a machinist at Los Alamos and provided sketches and descriptions of the implosion lens mold. While the Rosenberg ring provided valuable intelligence, it was less comprehensive than Fuchs's contributions.

Theodore Hall: The Young Volunteer

Theodore Hall was an 18, year-old prodigy working at Los Alamos when he independently decided to share atomic secrets with the Soviet Union. Unlike Fuchs, Hall was never prosecuted, Venona decrypts identified him only as "Mlad," but the evidence was not definitive enough for court. Hall admitted his activities only in 1997, shortly before his death.

Impact on the Soviet Atomic Program

The intelligence provided by Soviet spies fundamentally altered the timeline for Soviet development of atomic weapons. Without espionage, the Soviet Union would likely not have tested its first atomic bomb until the early 1950s.

Technical Assistance

Soviet scientists received detailed information about bomb design, uranium enrichment methods, and plutonium production. Klaus Fuchs provided specific data about the implosion-type plutonium bomb, including the complex explosive lens system necessary to compress the plutonium core. This information allowed Soviet scientists to avoid years of trial and error.

"When we received the intelligence data about the American work, it became clear that we were on the right track. The information helped us avoid many mistakes."

Time Saved

Western intelligence estimated that Soviet espionage accelerated the Soviet atomic bomb program by 18 months to 2 years. The Soviet RDS-1 test in August 1949 shocked American officials who had predicted the Soviets would not achieve atomic capability until at least 1952. This acceleration fundamentally altered the early Cold War balance of power.

Strategic Consequences

The early Soviet atomic bomb ended the American nuclear monopoly and created the bipolar nuclear standoff that defined the Cold War. The knowledge that espionage had facilitated this achievement intensified American concerns about internal security and contributed to the Red Scare of the late 1940s and 1950s.

The success of Soviet espionage also influenced Stalin's diplomatic strategy. Knowledge of American atomic capabilities, and the progress of the Soviet program, allowed Stalin to negotiate from a position of greater confidence at conferences like Yalta and Potsdam.

Discovery and Prosecution

The unraveling of Soviet atomic espionage began with the defection of Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko in Canada in 1945 and accelerated with the Venona decrypts. However, many spies were never identified or prosecuted during their lifetimes.

The Fuchs Confession

Klaus Fuchs was arrested in Britain in January 1950 after Venona decrypts identified him as the source of valuable atomic intelligence. Under interrogation, Fuchs confessed to passing information to the Soviets from 1943 to 1949. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison, the maximum possible under British law, as the Soviet Union was technically an ally during most of his espionage activities.

"I used my Marxist philosophy to establish in my mind two separate compartments. One compartment in which I allowed myself to make friendships... and another compartment in which I collected information."

The Rosenberg Case

Following Fuchs's arrest, investigators traced his courier Harry Gold, who implicated David Greenglass. Greenglass then testified against his sister and brother-in-law, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The Rosenbergs were convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage in 1951 and executed in 1953, the only civilians executed for espionage during the Cold War. Their case became a cause célèbre, with critics arguing that the evidence was insufficient and the punishment disproportionate.

Legacy and Historical Reassessment

The full extent of Soviet atomic espionage became clear only after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the declassification of the Venona Project files in 1995. These documents confirmed that Soviet espionage was far more extensive than previously known.

Venona Revelations

The Venona decrypts identified approximately 350 Americans who had had covert relationships with Soviet intelligence. Not all were spies, some were unwitting sources or contacts, but the scale of Soviet penetration shocked historians and the public. The decrypts confirmed the guilt of figures like Julius Rosenberg and Theodore Hall while clearing others who had been falsely accused.

Historical Controversy

The Rosenberg case remains controversial. While Venona confirms Julius Rosenberg's involvement in espionage, the evidence regarding Ethel is less clear. Some historians argue that she was executed primarily to pressure Julius into confessing. The case illustrates how espionage prosecutions became entangled with Cold War politics.

Fuchs in East Germany

After serving nine years in prison, Klaus Fuchs was released and emigrated to East Germany in 1959. He became a scientific administrator and received the Order of Karl Marx. Fuchs never expressed regret for his actions, maintaining that he had helped prevent American nuclear monopoly and balanced international power. He died in 1988, shortly before the Berlin Wall fell.

Espionage Timeline: 1942-1953

Operation ENORMOZ Begins

Soviet intelligence initiates systematic targeting of the Manhattan Project. NKVD and GRU establish networks in the United States.

Venona Project Starts

U.S. Army begins secret effort to decrypt Soviet intelligence messages, though significant breakthroughs remain years away.

Fuchs at Los Alamos

Klaus Fuchs arrives at Los Alamos and begins passing detailed technical information about bomb design to Soviet handlers.

Trinity Test

First atomic bomb tested at Alamogordo. Soviet intelligence provides detailed reports to Moscow within days.

Gouzenko Defection

Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko defects in Ottawa, revealing extensive Soviet spy networks in North America.

Continued Operations

Despite wartime alliance ending, Soviet espionage continues. Fuchs returns to Britain, continues passing information.

Fuchs Arrested

Klaus Fuchs arrested in Britain, confesses to atomic espionage. His testimony leads to other arrests.

Rosenberg Executions

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg executed at Sing Sing prison despite international protests.

12 Key Facts About Soviet Atomic Espionage

Operation ENORMOZ: The Soviet code name for intelligence operations targeting the Manhattan Project, involving multiple spy rings across the United States, Canada, and Britain.

Klaus Fuchs: The most valuable Soviet spy, a German-born British physicist who provided detailed designs of the implosion-type plutonium bomb from Los Alamos.

Venona Project: Secret American effort to decrypt Soviet messages, which eventually provided definitive proof of extensive espionage but remained classified until 1995.

Rosenberg Ring: Julius and Ethel Rosenberg coordinated a network including David Greenglass (machinist at Los Alamos) and courier Harry Gold.

Theodore Hall: An 18-year-old prodigy at Los Alamos who volunteered his services to the Soviets, identified only as "Mlad" in Venona decrypts.

Time Saved: Western intelligence estimated Soviet espionage accelerated the Soviet atomic program by 18 months to 2 years.

Stalin's Knowledge: Stalin knew about the American atomic bomb before Truman told him at Potsdam, thanks to intelligence reports from Soviet spies.

Ideological Motivation: Many spies were motivated by communist ideology and the desire to prevent American nuclear monopoly, not financial gain.

350 Identified: Venona decrypts identified approximately 350 Americans who had covert relationships with Soviet intelligence.

Fuchs's Sentence: Klaus Fuchs received only 14 years in prison because the Soviet Union was technically an ally during most of his espionage.

Rosenberg Controversy: While Julius Rosenberg was definitely a spy, evidence regarding Ethel's direct involvement remains ambiguous.

East German Welcome: After his release in 1959, Fuchs became a scientific administrator in East Germany and received the Order of Karl Marx.

— Igor Kurchatov, head of Soviet atomic project

Frequently Asked Questions

Continue Reading

← Previous

Next →

On This Page

Key Spies

- Klaus Fuchs — Physicist

- Julius Rosenberg — Coordinator

- Ethel Rosenberg — Courier

- David Greenglass — Machinist

- Harry Gold — Courier

- Theodore Hall — Physicist

Key Events

- 1942: ENORMOZ begins

- 1944: Fuchs at Los Alamos

- 1950: Fuchs arrested

- 1953: Rosenbergs executed

- 1995: Venona revealed

Related Articles

The abbreviation was widely used on official documents, currency, and state symbols of the Soviet Union.

The iconic sculpture "Worker and Kolkhoz Woman", created by Vera Mukhina for the 1937 World's Fair in Paris.

About This Article

This article examines Soviet espionage in the Manhattan Project from 1942 to 1953. Part of the Cold War series on soviet-union.com

Last Updated: February 17, 2026 | Reading Time: 15 minutes