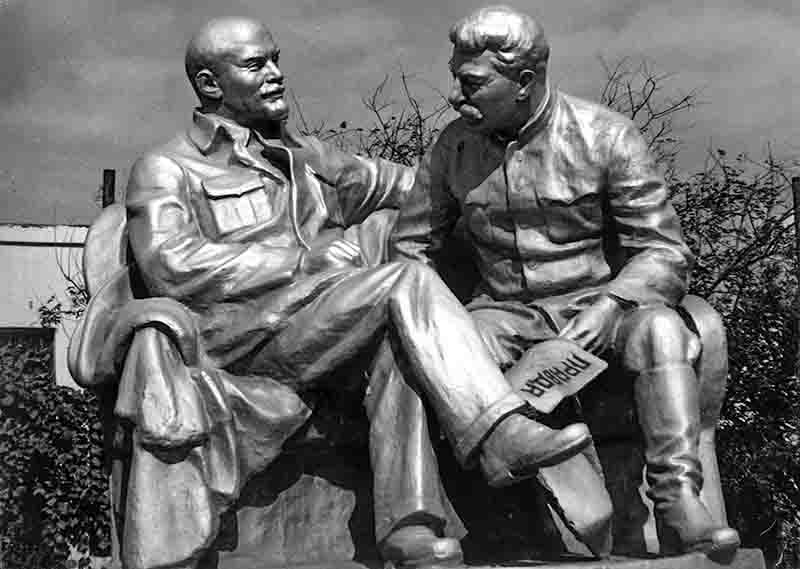

Statues of Lenin and Stalin could be found in various places in the Soviet Union, including the Moscow Metro. There were two standard designs: one where the two leaders sat together on a bench, and one where Lenin sat and Stalin stood. Such statues were removed as part of Khrushchev's policy of de-Stalinization in the early 1960s.

Socialist Realism was a Soviet art movement that dominated art production from the early 1930s to the late 1980s. The style was mandated by the state and intended to promote socialist ideology by depicting scenes of everyday life, especially the work and recreation of ordinary people.

Socialist Realism served as a powerful tool of propaganda for the Soviet Union, aiming to shape public consciousness and reinforce the ideals of communism. The primary target audience for socialist realism was the "common man," particularly the workers in factories and agricultural sectors.

This focus stemmed from the communist ideal of elevating the proletariat and portraying their lives as admirable examples of socialist virtue. Socialist Realism aimed to present an optimistic and romanticized view of life in the USSR. This involved showcasing the "health and happiness" of the Soviet people, highlighting industrial and agricultural progress, and celebrating the heroism of workers and other model citizens.

Art as Ideological Weapon

Unlike Western art movements that evolved through artistic debate and market forces, Socialist Realism was decreed from above. In 1932, the Soviet state officially adopted it as the only acceptable artistic style. This made the Soviet Union unique: never before had a modern state so systematically controlled artistic production to serve explicit political goals.

Political and Ideological Foundation

The early Soviet period saw the flourishing of avant-garde art. However, by the 1930s, the government deemed it "arid," "soulless," and "formalist," favouring a more accessible and didactic style for the masses. Socialist realism, as an artistic movement, was officially mandated in the 1930s during Joseph Stalin's leadership in the Soviet Union.

The 1934 Zhdanov Doctrine

This wasn't just a preference for a particular artistic style; it was a state-imposed directive. Art, in all its forms—literature, music, painting, and sculpture—was expected to serve the goals of socialism. The primary objective was clear: create art that portrayed the strength and unity of the working class, the inevitability of the communist future, and the virtues of the Soviet or socialist regime.

Proletarian

Relatable to Workers

Art must be understandable and accessible to the working class, avoiding bourgeois elitism.

Typical

Show Everyday Life

Depict scenes from daily life that resonate with the experiences of ordinary Soviet citizens.

Realistic

Representational Style

Employ realistic techniques while idealizing subjects—showing life as it should be under communism.

"A combination of the most austere, sober, and practical work with supreme heroism and the most grandiose prospects."

The Partisan Principle

The fourth requirement—Partisan—meant art must be supportive of the state and Party. This went beyond mere political neutrality; artists were expected to actively promote communist ideals. The "Partisan" nature of Socialist Realism made it unique among 20th-century art movements: it was explicitly created to serve a political party's interests.

The Role of Propaganda

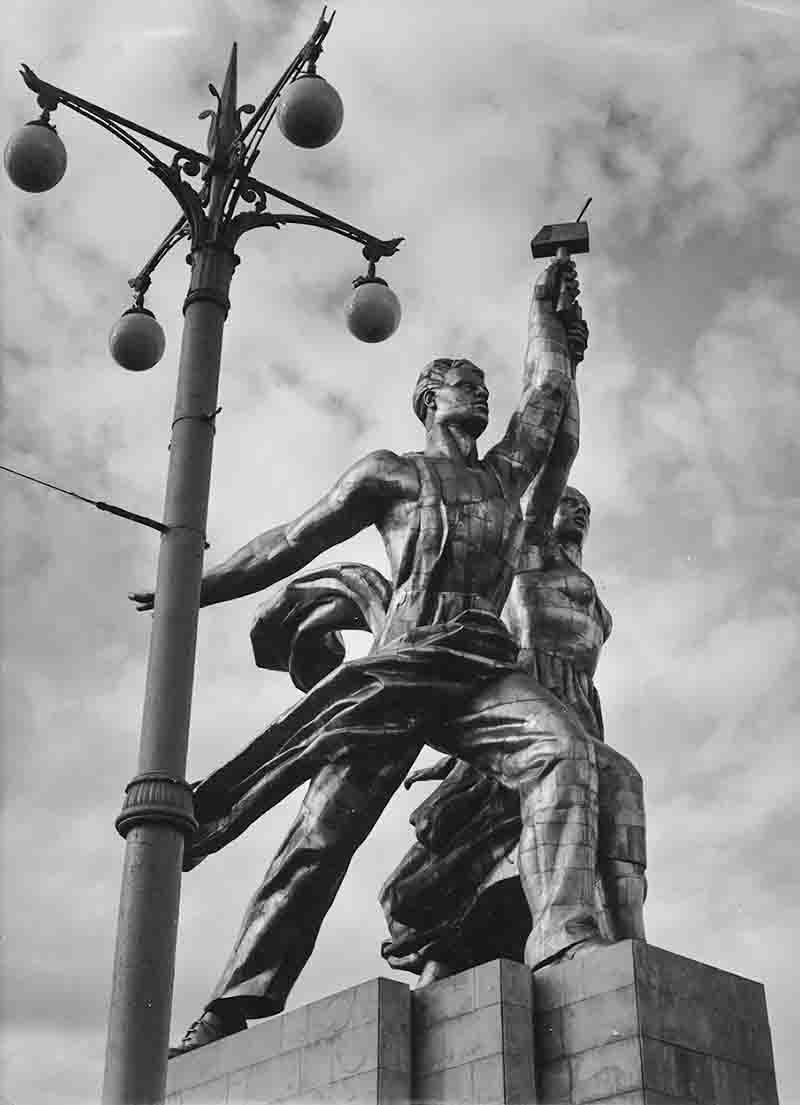

Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, the pair is meant to represent the eternal unity of the working class and the peasantry in the Soviet Union. During the 1937 World's Fair in Paris, a confrontation took place between the two future enemies of the Second World War, the USSR and Germany. Their monumental pavilions were directly opposite each other on the main boulevard at the Trocadéro.

Creating the "New Soviet Man"

The concept of the "New Soviet Man" was central to socialist realism sculptures. This idea envisioned a new type of human being—one who was entirely selfless, hardworking, and deeply committed to the ideals of socialism. Soviet art depicted this ideal man as physically strong, emotionally disciplined, and mentally focused.

Glorification of Labor

• Workers portrayed with exaggerated physiques

• Factory and field labor as noble endeavors

• Tools of labor as symbols of progress

• Unity across industrial and agricultural sectors

Heroic Citizens

• Revolutionary leaders immortalized

• Soldiers depicted as defenders of socialism

• Women as strong workers and mothers

• Youth dedicated to communist future

Accessible to the Masses

To effectively reach the widest possible audience, Socialist Realism employed a readily understandable realistic style. Unlike abstract or avant-garde art that might confuse or alienate workers, Socialist Realism was immediately legible. This accessibility was crucial for its function as propaganda—every citizen, regardless of education, could understand the message.

Navigating Censorship: Art in the Soviet Union

With the institution of Socialist Realism as the official art style in 1932, the Soviet state, under Stalin's rule, exerted tight control over artistic expression, dictating acceptable themes, styles, and messages. This control had far-reaching consequences for artists, forcing them to navigate a complex web of restrictions to avoid persecution and advance their careers.

Consequences for Non-Compliance

Transgressions against the Soviet art principles were met with harsh punishments. Artists who dared to deviate from the prescribed path faced a range of consequences, from exclusion from prestigious unions, which acted as gatekeepers to exhibition opportunities, to social ostracism, loss of livelihood, and even imprisonment.

"This created a climate of fear and self-censorship among artists, who often had to choose between their creative impulses and personal safety."

Strategies of Resistance

Despite the suffocating grip of censorship, artists developed various strategies to navigate these restrictions, preserve their artistic integrity, and find avenues for personal expression. While the state sought to create a unified style, individual artists still managed to express their own creativity, which is now being recognised by art historians.

Some artists found ways to inject their own unique creativity and nuance into their works, bypassing the confines of Socialist Realism. They subtly undercut expectations, tackling established themes in intriguing ways and creating independent works that did not conform to the official style.

Historical Timeline

From the early 1930s to the 1980s, socialist realism reigned as the officially sanctioned art style in the USSR, shaping painting, sculpture, literature, and other art forms. The following timeline traces the evolution of this state-mandated artistic movement.

Official Adoption

The Soviet Union officially adopts socialist realism as the state-approved artistic style, including sculpture. The state becomes the sole patron of the arts.

Zhdanov's Formula

Central Committee delegate Andrei Zhdanov outlines the formula for Socialist Realism: "A combination of the most austere, sober, and practical work with supreme heroism and the most grandiose prospects."

Paris World's Fair

The iconic "Worker and Kolkhoz Woman" sculpture premieres at the Paris World's Fair. Soviet and German pavilions face each other at the Trocadéro, foreshadowing the coming conflict.

World War II

During WWII, socialist realism art focuses on themes of patriotism and heroism, reflecting the war effort. Art becomes a tool for national unity and resistance.

Expansion to China

Socialist realism becomes the dominant art style in China, influencing the creation of state art under Mao Zedong's regime. The movement spreads beyond Soviet borders.

Peak Production

Significant socialist realism artworks are created in the Soviet Union, symbolizing unity between workers and peasants. The style reaches its mature form.

Artistic Challenges

Emergence of notable artists working within (and sometimes challenging) the confines of Socialist Realism. Some begin seeking subtle avenues for personal expression.

The Severe Style

Rise of the "Severe Style" within Socialist Realism—a more austere, less idealized approach that still adhered to state principles but showed greater psychological depth.

Waning Influence

The influence of socialist realism begins to wane as modernist and abstract art styles gain popularity. Underground art movements begin to challenge state dominance.

Western Exhibitions

Exhibitions of Soviet socialist realism art are held in Western countries, showcasing Soviet artistic achievements to international audiences for the first time in decades.

Soviet Dissolution

The dissolution of the Soviet Union leads to a reassessment of socialist realism art and their place in history. State funding collapses; artists gain freedom but lose support.

Restoration Begins

Significant restoration projects for socialist realism begin, led by newly formed independent institutions. Preservation debates emerge about communist monuments.

Academic Reassessment

Conferences and symposiums are held globally to discuss the historical and artistic significance of socialist realism. Scholarship moves beyond Cold War polemics.

Growing Interest

Growing interest in socialist realism as a subject of academic research and public exhibitions. Museums begin collecting and displaying works as historical artifacts.

Global Recognition

Major museums around the world host exhibitions dedicated to socialist realism, emphasizing its historical context and artistic value beyond propaganda.

A Western Eye on Soviet Art

Rooted in realism, Socialist Realism went beyond mere representation, demanding historical accuracy intertwined with optimism and the "revolutionary potential" of society.

The 1956 Breakthrough

In 1956, Peter Bock-Schroeder became the first West-German photo reporter to visit the Soviet Union and was given the opportunity to portray the Russian sculptor Matvey Manizer at work in his atelier in Leningrad.

A Rare Western Perspective

Bock-Schroeder's 1956 journey was unprecedented. At the height of the Cold War, when most Western journalists were barred from the USSR, he gained access to document Soviet life—including the artists creating Socialist Realist works. His photographs provide a unique outsider's view of how these monumental sculptures were actually produced, showing the human hands behind the ideological monoliths.

This documentation is particularly valuable because it captures Socialist Realism not as finished propaganda, but as a living artistic practice. Bock-Schroeder's images of Matvey Manizer—one of the most prominent Socialist Realist sculptors—reveal the technical skill and artistic dedication that existed within the constraints of state-mandated style.

Key Themes and Subjects

The Protagonists of Socialist Realism

By depicting heroic workers, diligent farmers, and joyful citizens, Socialist Realism sought to instill a sense of pride and belief in the Soviet system. While men were often the focus, women also appeared, depicted as peasants or workers but still embodying the same strength and determination as their male counterparts.

Industrial Workers

• Factory laborers with muscular physiques

• Steelworkers and miners as heroes

• Industrial progress and machinery

• Five-year plan achievements

Collective Farmers

• Strong, weathered peasants

• Kolkhoz (collective farm) scenes

• Agricultural abundance and harvests

• Urban-rural unity

Revolutionary Leaders

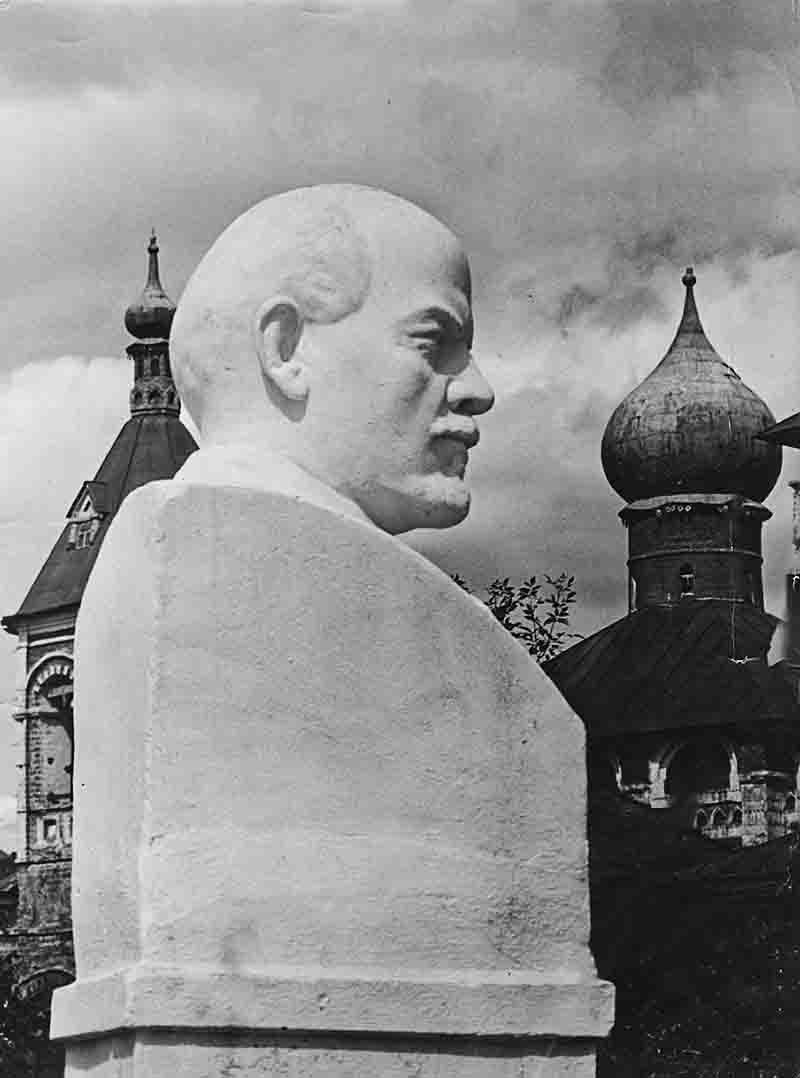

Socialist Realism immortalized revolutionary leaders like Lenin and Stalin, positioning them as central figures in the nation's narrative. Lenin was typically depicted as the wise founder, while Stalin appeared as the continuer of his work. After 1956, Stalin's image was systematically removed as part of de-Stalinization, while Lenin remained a constant presence.

While Socialist Realism remains most closely associated with the Soviet Union, its influence extended beyond its borders, particularly in countries with communist or socialist governments.

The Legacy: A Contested Terrain

As symbols of a specific time and place, they remain a testament to the power of art as a tool of political control.

The legacy of Socialist Realism remains a subject of ongoing debate and reassessment. Its initial reputation as a purely propagandistic and artistically stifled movement is gradually giving way to a more nuanced understanding that recognizes its complexities, its achievements, and its influence on both Russian and global art.

Artistic Skills vs. Ideological Constraints

Soviet art schools emphasised traditional techniques like drawing and painting from life models. This resulted in artists who were highly skilled in realistic representation and linear accuracy. While the ideological constraints were severe, the technical training produced artists capable of remarkable craftsmanship.

"By combining realistic aesthetics with idealized portrayals of Soviet life and communist ideals, Socialist Realism served as a highly effective propaganda tool. It aimed to cultivate a sense of national unity, instill faith in the Communist Party, and mold citizens into the 'New Soviet Man', ultimately solidifying the power and legitimacy of the Soviet state."

While its limitations are undeniable, Socialist Realism serves as a reminder of the intricate relationship between art, politics, and society, and the ways in which artists have navigated the challenges of censorship and ideological control throughout history. By understanding the political climate, the ideological imperatives, and the everyday realities of life in the Soviet Union, scholars have been able to uncover layers of meaning and nuance within Socialist Realism that were often overlooked during the Cold War era.

12 Key Facts About Socialist Realism

State-Sponsored Art: Socialist realism was primarily state-sponsored and served as a tool for promoting the ideology of socialist and communist regimes.

Ideological Purpose: These works depicted idealized figures such as workers, peasants, soldiers, and revolutionary leaders, symbolizing collective strength, industrial progress, and dedication to socialist values.

Official Mandate: In 1932, Socialist Realism became the only officially approved artistic style in the Soviet Union—a unique example of state-controlled art.

Realistic Style: Unlike modernist or abstract art, socialist realism embraced a realistic, accessible style to ensure the message was clear and understandable to the masses.

Key Countries: Socialist realism was prominent in the Soviet Union, China, North Korea, Cuba, and other socialist states, each adapting the style to reflect their own revolutionary history.

Glorification of Labor: Soviet state art focused on the glorification of industrial and agricultural labor, portraying workers as heroic figures driving progress.

Propaganda Tool: The primary function of socialist realism was propaganda, aiming to reinforce loyalty to the state and promote collective effort over individualism.

Rejection of Avant-Garde: Socialist realism was enforced at the expense of avant-garde, abstract, and experimental art movements, which were seen as elitist or counter-revolutionary.

Regional Variations: Socialist Realism had different manifestations in different regions, reflecting unique social and political contexts of each place.

Representation of Leaders: Socialist Realism immortalized revolutionary leaders like Lenin, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Kim Il-sung, positioning them as central figures in national narratives.

Artist Employment: In the Soviet system, artists became state employees, receiving salaries and benefits but sacrificing artistic freedom to adhere to state-mandated styles.

Decline After 1991: While Socialist Realism was a powerful force in the 20th century, its influence began to wane with the end of the Soviet Union, though its monuments remain.

These facts highlight the political, artistic, and social significance of socialist realism during the 20th century.

Frequently Asked Questions

Art had to be: Proletarian (relatable to the workers), Typical (showing everyday life), Realistic (in a representational style), and Partisan (supportive of the state and Party).

The early Soviet government initially embraced the Avant Garde, seeing radical art as aligned with revolutionary ideals. However, by the 1930s, they sought greater control over art, favouring the accessible and propagandistic style of Socialist Realism.

Artists faced serious consequences for non-compliance, ranging from expulsion from the Komsomol or Party to imprisonment in gulags or even execution, particularly during the "Terror" of the 1930s.

The "new Soviet Man" represented the idealised citizen of the communist state, embodying hard work, dedication, and optimism. Socialist Realism aimed to promote this ideal by depicting workers and their lives in a heroic and positive light.

Socialist Realism aimed to depict everyday life, particularly the lives of workers, but only in a highly idealised manner that glorified labour and omitted any negative aspects of Soviet society.

Socialist Realism drew upon Neoclassicism, Russian realism of the 19th century (particularly the Peredvizhniki movement), and the works of artists like Jacques-Louis David and Ilya Repin.

In the Soviet system, the state became the sole patron of the arts. Artists became state employees, receiving salaries and benefits but sacrificing artistic freedom as they were expected to adhere to state-mandated styles and subjects.

Soviet art schools emphasised traditional techniques like drawing and painting from life models. This resulted in artists who were highly skilled in realistic representation and linear accuracy.

The dissolution of the Soviet Union led to a reassessment of socialist realism art. State funding collapsed, artists gained freedom but lost support, and preservation debates emerged about communist monuments. Major museums now host exhibitions recognizing its historical significance.

Continue Reading

← Previous Russophobia: A Persistent Shadow

Next → CCCP: The Soviet Symbol

On This Page

Four Requirements

Proletarian: Relatable to workers

Typical: Show everyday life

Realistic: Representational style

Partisan: Support state/Party

Key Data

Period: 1930s — 1980s

Status: State-mandated only style

Key Figure: Andrei Zhdanov (1934)

Focus: Workers, peasants, heroes

Scope: USSR, China, Cuba, DPRK

Related Articles

Download

Get the complete Socialist Realism research documents and artist profiles.

Socialist Realism PDF (Available 15.3.26)

The centuries-old phenomenon of fear, mistrust, and hostility toward Russia, its people, and its culture.

The historic meeting of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin that shaped postwar Europe.

About This Article

This article examines Socialist Realism—the officially sanctioned art movement of the Soviet Union from the 1930s-1980s—exploring how art served as state propaganda, the role of artists under communism, and the complex legacy of this controversial movement. Part of the Soviet Union Blog on soviet-union.com

Last Updated: February 13, 2026 | Reading Time: 18 minutes