Matvey Manizer was a Soviet sculptor known for his monumental works in the socialist style. He created public sculptures that glorified Soviet leaders and ideals, including statues of Lenin and Stalin. Manizer's detailed bronze and marble works played a key role in promoting Soviet propaganda and shaping national identity.

Manizer played a key role in creating art that aligned with Soviet ideology, focusing on themes like revolutionary heroes, industrial labor, and national pride.

Matvey Manizer's sculptural works are an essential part of the art history of the Soviet Union.

Born in 1891 in Saint Petersburg, Manizer made a name for himself through his monumental socialist realism style that aligned perfectly with the state’s propaganda goals.

He worked primarily with bronze and marble, creating works that can still be seen across Russia and other former USSR.

His sculptures of Lenin, Stalin, and other Soviet icons were not just artistic expressions—they were key pieces of Soviet propaganda.

Manizer’s art served the state, helping to construct a visual narrative of power, heroism, and the collective good.

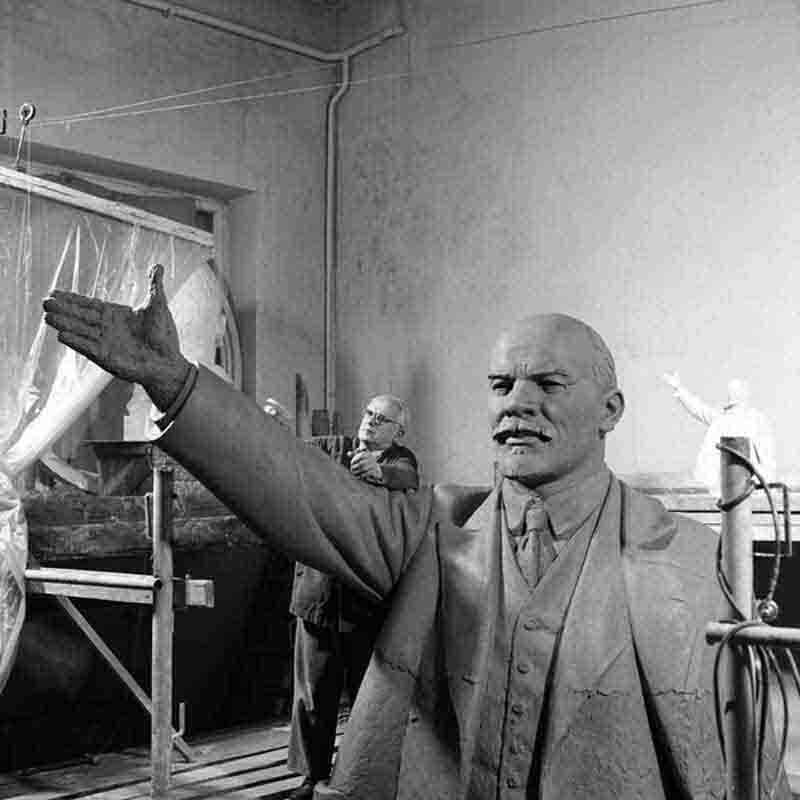

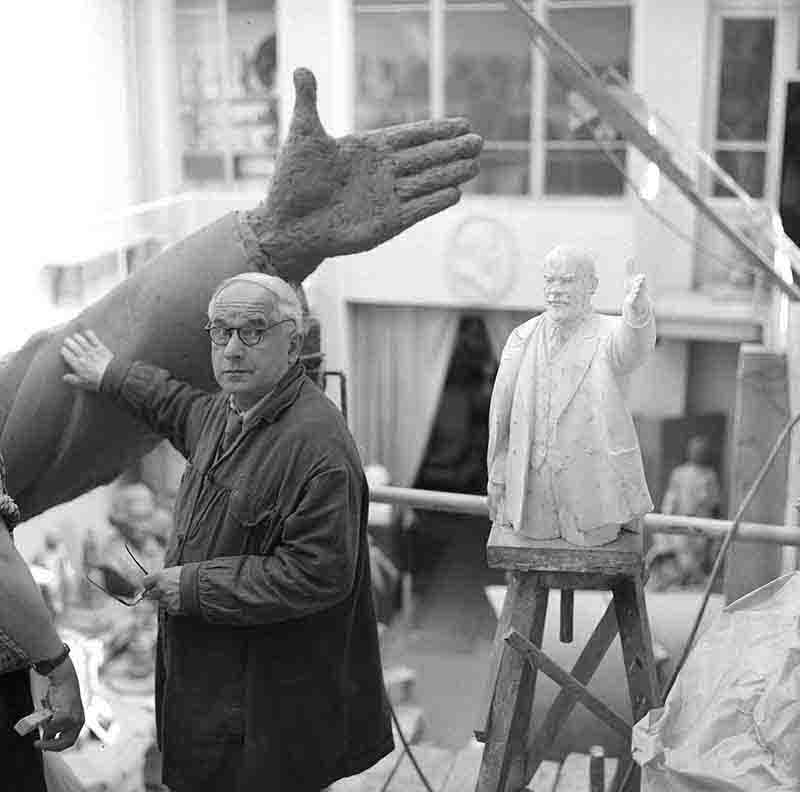

In 1956, during his one-year photo tour of the Soviet Union, West German photojournalist Peter Bock-Schroeder visited Manizer in his Leningrad studio and documented the master sculptor at work.

12 key facts about Matvey Manizer

-

Birth and Background: Matvey Manizer was born in 1891 in Saint Petersburg, Russia, to a family with German roots, which later integrated into Soviet society.

-

Early Life and Education: Manizer was trained not only as a sculptor but also as a painter, which gave him a broader understanding of composition and form.

-

Soviet Public Art: His sculptures focused on glorifying Soviet ideals, leaders, workers, and soldiers, aligning with the state's propaganda efforts.

-

Monumental Works: Manizer is renowned for his large-scale public monuments, such as statues of Lenin and Stalin, as well as memorials dedicated to Soviet revolutionary figures.

-

Key Works: Notable works include the statues of Soviet leaders at the Moscow Metro stations, the Maxim Gorky monument, and the monumental "Workers of the World Unite" sculpture.

-

Technical Expertise: He was highly skilled in working with materials such as bronze and marble, often creating technically precise and lifelike representations of his subjects.

-

Stalin Prize Winner: Manizer was a recipient of multiple Stalin Prizes, one of the highest state honors in the USSR, for his artistic achievements and contributions to Soviet culture.

-

Teacher and Mentor: Beyond his work as a sculptor, Manizer was a respected professor at the Leningrad Academy of Arts, where he mentored a generation of Soviet artists and sculptors.

-

World War II Influence: During and after World War II, his work contributed to memorials honoring Soviet soldiers and the war effort, reinforcing the narrative of Soviet heroism.

-

National Identity: Manizer’s sculptures played a significant role in shaping Soviet national identity, particularly in the creation of memorials that reinforced collective memory and patriotism.

-

Family Legacy: Manizer's wife, Elena Yanson-Manizer, was also a notable sculptor, and his son, Genrikh Manizer, followed in his footsteps as an artist, continuing the family’s artistic legacy.

-

Death and Legacy: Matvey Manizer passed away in 1966, leaving behind a legacy of monumental works that remain key examples of Soviet cultural history.

These facts highlight Matvey Manizer's contributions to Soviet art and culture, as well as his technical expertise in sculpture.

Matvey Manizer: Timeline

Educated at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, Manizer became renowned for his large-scale sculptures.

His legacy is studied for its role in both Soviet cultural history and the development of monumental sculpture.

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 1891 | Matvey Manizer is born on January 8 in the village of Orenburg, Russia, into a family of Jewish descent. |

| 1911 | Manizer begins studying at the Orenburg Art School, where he starts to develop his artistic skills. |

| 1916 | Manizer enrolls in the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg (now Saint Petersburg State Academic Institute of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture). He studies under prominent instructors, including the sculptor Sergey Zaryanko. |

| 1921 | Manizer graduates from the Academy of Arts. He begins to establish himself in the art world with a focus on sculpture. |

| 1920s | Manizer starts producing works that reflect the influence of modernist movements, although he later transitions to a style that aligns with Soviet ideology. |

| 1930 | Manizer’s work begins to reflect the ideological and political requirements of the time. He becomes known for his monumental sculptures. |

| 1932 | Manizer is commissioned to create a significant piece for the Soviet government, marking his entry into the realm of large-scale, state-sponsored public art. |

| 1935 | He completes the “Victory Monument” in Moscow, celebrating Soviet achievements. |

| 1937 | Manizer’s work gains international attention when he participates in the International Exhibition in Paris, showcasing Soviet art on a global stage. |

| 1939 | Manizer contributes to the Soviet war effort with sculptures that boost morale and reflect wartime themes. His works during this period often celebrate Soviet strength and resilience. |

| 1941-1945 | During the Second World War, Manizer creates several works to honor Soviet soldiers and commemorate wartime victories. His art becomes a symbol of Soviet perseverance and patriotism. |

| 1949 | After the war, Manizer is commissioned for several new public works, including monuments and statues celebrating Soviet leaders and ideological achievements. |

| 1950 | Manizer officially retires from his active role in the art world, though he remains involved in various artistic and cultural projects. |

| 1953 | he death of Joseph Stalin marks a significant shift in Soviet art. Manizer’s works, deeply tied to the Stalinist era, are reassessed in the changing political climate. |

| 1957 | The Soviet Union recognizes Manizer’s contributions to art with posthumous awards and exhibitions. His work is revisited in the context of Soviet history and art |

| 1961 | Major exhibitions are held to celebrate Manizer’s life and work. His sculptures are included in retrospectives that highlight his impact on Soviet art and Socialist Realism. |

| 1966 | Matvey Manizer passes away in 1966 and is laid to rest at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow. |

| 1980s | As the Soviet Union undergoes cultural and political changes, there is a renewed interest in Manizer’s work. Scholars and critics reassess his contributions in the broader context of Soviet art. |

| 1991 | The dissolution of the Soviet Union leads to a re-evaluation of Socialist Realism and its artists, including Manizer. His work is studied for its role in Soviet ideology and culture. |

| 2000s | Manizer’s works are subject to restoration projects to preserve their historical and artistic value. New exhibitions focus on his contributions to Soviet public art and propaganda. |

| 2010s | Research into Manizer’s life and work continues, with publications and academic studies exploring his role in Soviet art history and the impact of his sculptures. |

| 2020s | Matvey Manizer’s legacy is maintained through educational programs, museum exhibitions, and scholarly research. His work is discussed in the context of its historical significance and artistic contributions. |

This timeline provides a comprehensive overview of Matvey Manizer’s life, career, and the evolving perception of his work throughout Soviet and post-Soviet history.

The Artistic Vision of Matvey Manizer in Soviet Propaganda

Manizer’s sculptures are characterized by their large scale, technical precision in bronze and marble, and their role in Soviet propaganda.

Early Life and Education of Matvey Manizer

Matvey Manizer was born March 5th 1891 in St. Petersburg, into the family with German roots.

Growing up in Saint Petersburg, Manizer witnessed significant political and social changes that would shape his worldview.

His father, Henry Manizer, was a sculptor himself, which likely influenced young Matvey’s choice to pursue art.

As a student he attended the Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, and from 1911 through 1916 the art school of the Peredvizhniki.

The Academy was known for its rigorous classical education, with a focus on ancient and European art traditions.

Established in 1870, The Society for Itinerant Art Exhibitions, commonly known as Peredvizhniki - meaning "Itinerants" or "Wanderers" - believed in representing subject-matter drawn from everyday life, with an accuracy and empathy which reflected their egalitarian social and political views.

This early training laid the groundwork for Manizer's technical expertise, but his future path took a dramatic turn after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

While the classical foundation never left him, Manizer had to adapt his style to meet the demands of the new Soviet state.

Artists now wanted to serve the construction of a new society.

In the 19th century, before Stalin and his art dictates, there were precursors of reality-based art that aimed to portray workers with a sense of grandeur and dignity.

Influences on Manizer’s Work

Manizer’s sculptures were part of the USSR’s broader effort to instill a sense of national pride and identity

Manizer’s early exposure to classical art forms was critical in his development as an artist.

Sculptors like Michelangelo and Rodin were key influences.

From these masters, he learned the importance of physical detail and the portrayal of strength and emotion in sculpture.

These influences can be seen in his later works, which, while conforming to the ideals of socialist realism, retained a degree of emotional depth.

In the 1920s, Manizer's career began to shift in alignment with the Soviet regime's focus on socialist realism.

Soviet leaders wanted art that glorified the worker and the collective over the individual.

This shift is evident in Manizer’s work as he moved from the classical styles of his early career to a more state-driven artistic expression.

His figures became more rigid, their expressions solemn, as they symbolized the ideal Soviet citizen.

From 1926 Manizer was a member of the "Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia", later known as the "Association of Artists of the Revolution".

Various members of this group of Soviet artists won favour as legitimate bearers of communist ideas in the world of art and formulated the framework for the state-prescribed style.

Matvey Manizer’s Role in Propaganda

Through his mastery of bronze and marble, Manizer created works that continue to stand as symbols of a bygone era.

Although the art of the Soviet Union also contained modern elements, the Futurists sounded the alarm in 1928.

They feared the loss of pluralism and artistic freedom.

In 1932, under Josef Stalin, the Central Committee of the CPSU declared socialist realism to be the valid and binding aesthetic of the Soviet Union, which was to last until the collapse of the USSR.

A "reorientation of the fine arts towards political agitation and propaganda" was demanded by the author N. Malenikov in 1931 in his report on a traveling exhibition of the art sector of the People's Commissariat of Education.

The party dictates of true socialism replaced the diversity of avant-garde art.

Paintings titled "Building a Factory" or "Life is Getting Better" were now created according to Stalin's art policy.

The pluralism of the arts, which had existed immediately after the October Revolution in Lenin's time, was now history.

For an artist like Manizer, this meant creating works that were both accessible and deeply political.

Sculptors were tasked with not only depicting reality but doing so in a way that aligned with the Soviet vision of a perfect socialist society.

Manizer excelled in this environment. His ability to combine classical techniques with the demands of Soviet Union State art made him a favorite of Soviet leaders.

His sculptures were monumental in scale and placed in public spaces where they could be seen by thousands of people daily.

They were tools of the state, used to control public perception and enforce a narrative of unity and strength.

Key Elements of Manizer’s Work

By creating larger-than-life depictions of Soviet heroes, he helped solidify their place in the Soviet consciousness.

Manizer's statues were prime examples of Soviet sculpture.

The subjects he portrayed were often workers, soldiers, and peasants—the people who, in the eyes of the state, represented the backbone of the Soviet Union.

These figures were almost always shown in heroic poses, their faces expressing determination and optimism.

This was intentional. The goal was not just to represent these people but to idealize them as symbols of the Soviet future.

One of the most notable elements of Manizer’s work is his portrayal of leaders like Lenin and Stalin.

These figures were depicted larger than life, their features idealized to the point of near perfection.

The leaders were not just men in these sculptures—they were icons of the revolution and the socialist future.

Their placement in public spaces further emphasized their symbolic role as guides for the people.

The Role of Monumental Sculpture in Soviet Society

Matvey Manizer’s career exemplifies the intersection of art and politics in Soviet history.

Soviet monumental sculptures were more than just art; they were powerful tools for shaping public opinion.

The government strategically placed these sculptures in high-traffic areas—metro stations, city squares, and public parks—ensuring that Soviet citizens would constantly be reminded of the state’s ideals.

Manizer’s sculptures, in particular, were used to convey a sense of power and permanence.

His massive figures, often standing several meters tall, were impossible to ignore.

They represented not just the individuals they depicted but the state itself.

Through these works, the Soviet government could reinforce the idea that the socialist system was unbreakable, and its leaders were almost divine in their wisdom and strength.

In 1941 Manizer moved to Moscow. Working in an academic and realistic style, Manizer produced a great number of monuments situated throughout the Soviet Union, including some twelve portrayals of Lenin.

During the Great Patriotic War, in 1943 he donated the awarded Stalin Prize (the sum of 100 000 rubles) to the defense Fund.

Manizer was awarded the "People's Artist of the USSR" (1958), "Member of USSR Academy of Arts" (1947).

He was vice president of USSR Academy of Arts (1947-1966), chairman of the Saint Petersburg Union of Artists from 1937 to 1941, and winner of the "Stalin Prize" three times.

in 1953 he was the author of Stalin’s bronze death masks.

In 1966 he became vice-president of the USSR Academy of Arts.

Techniques and Materials in Manizer’s Sculptures

Whether it was a worker, a soldier, or a leader, each figure was portrayed as a hero, worthy of admiration and emulation.

Manizer was a technical master, known for his exceptional skill in working with bronze and marble.

These materials allowed him to create sculptures that were not only visually striking but also durable enough to withstand the elements and the passage of time.

The techniques he used were essential to the success of his monumental works, particularly because many of them were placed in outdoor public spaces where they needed to endure the harsh Soviet winters.

Bronze Sculpting Techniques

Bronze was one of Manizer’s preferred materials.

It provided the durability needed for large public sculptures while also allowing for a high level of detail.

Manizer used the lost-wax casting method to produce his bronze sculptures, a technique that involves creating a model in wax, covering it in clay or another heat-resistant material, and then melting the wax to leave a mold.

This process allowed him to capture even the smallest details, from the folds of a worker’s overalls to the intense expression on a soldier’s face.

Manizer’s bronze sculptures were more than just representations of people; they were symbols of strength and endurance.

The material itself contributed to this symbolism. Bronze, being both strong and malleable, reflected the ideals of the Soviet worker—tough yet adaptable, capable of overcoming any obstacle.

Marble Work

While bronze allowed for more intricate detailing, Manizer’s marble sculptures were equally impressive.

Marble, a softer material, required a different set of skills.

Manizer often used marble for portraits and smaller public works, where the goal was to convey a sense of dignity and softness rather than raw power.

The smooth surfaces of his marble works contrasted with the rougher, more industrial feel of his bronze sculptures.

This contrast allowed him to explore different aspects of Soviet life.

For example, a marble bust of a poet or writer could capture the intellectual side of the revolution, while a bronze statue of a soldier represented its physical strength.

Major Works and Their Political Significance

His sculptures were part of a larger effort to control public perception and enforce the state’s narrative.

Manizer’s works were not created in a vacuum. Each sculpture had a specific political purpose, whether it was reinforcing the power of the state or promoting the ideals of the revolution.

His most famous works were large-scale public sculptures of Soviet leaders, including Lenin and Stalin, as well as monuments to key figures in Soviet culture and history.

Lenin and Stalin Statues

One of Manizer’s most recurring subjects was Vladimir Lenin, the founder of the Soviet state.

Lenin statues were common throughout the Soviet Union, but Manizer’s stood out for their size and attention to detail.

Lenin was often depicted in a commanding pose, either addressing a crowd or deep in thought.

The purpose of these sculptures was clear: to show Lenin as a man of action and intellect, the ideal leader of the proletariat.

Similarly, Manizer’s statues of Stalin were designed to elevate the Soviet leader to a near-mythical status.

In these works, Stalin was often portrayed as a fatherly figure, guiding the Soviet people through difficult times.

His features were softened to make him appear more approachable, yet the sheer size of the statues conveyed his power and authority.

Gorky Monument

Matvey Manizer’s sculptures were more than just artistic creations; they were essential components of the Soviet Union’s effort to build a national identity.

The Maxim Gorky Monument was one of Manizer’s most culturally significant works.

Gorky, a famous Soviet writer, was seen as a key figure in promoting socialist ideals through literature.

By creating a monument to him, Manizer not only honored Gorky’s contributions to Soviet culture but also reinforced the importance of intellectuals in the revolution.

This monument was placed in a prominent public space, ensuring that it would be seen by thousands of people every day.

Its placement was strategic, as it linked Gorky’s legacy with the larger goals of the Soviet state.

In this way, Manizer’s work went beyond mere representation—it became a tool for shaping public memory

Moscow Metro Sculptures

The Moscow Metro is often referred to as an underground palace, and Manizer’s sculptures played a significant role in achieving that effect.

His works, which lined the walls of many metro stations, depicted workers, soldiers, and peasants in idealized forms.

These sculptures were meant to inspire pride in the Soviet way of life and remind commuters of their role in building the socialist state.

Each sculpture was carefully crafted to fit within the architectural design of the metro, blending seamlessly with the grandiose marble columns and ornate ceilings.

The metro itself was a symbol of Soviet progress, and Manizer’s sculptures added a human element to this larger narrative of industrial achievement.

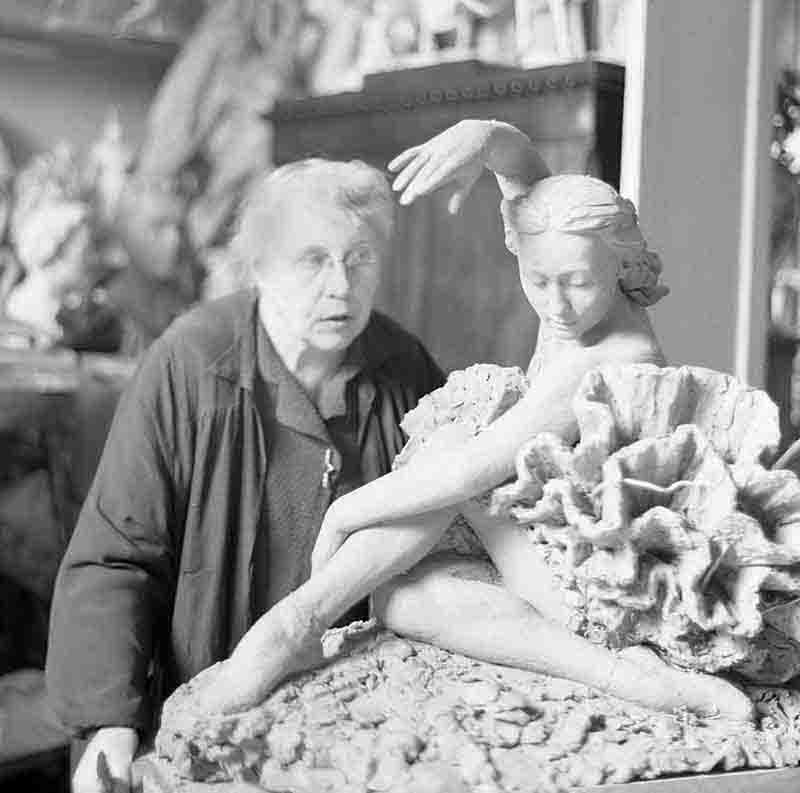

The Sculptural Legacy of Elena Yanson-Manizer

Alexandrovna Yanson-Manizer worked primarily in bronze and marble, creating sculptures that often depicted revolutionary heroes, workers, and scenes of socialist life.

Manizer's wife Elena Alexandrovna Yanson-Manizer (1890-1971) was a sculptor in her own right, with work at the Dynamo station of the Moscow Metro.

Their son Hugh Matveyevich Manizer (born 1927) is a noted painter.

Among Manizer's students was the Stalin Prize-winning Fuad Abdurakhmanov.

Yanson-Manizer: A Leading Female Sculptor

Many of her sculptures were designed for public spaces, emphasizing themes of collective labor and the glorification of the Soviet state.

Elena Janson-Manizer or Yanson-Maniser was the 20th century's leading sculptor of the Soviet ballet.

Her beautiful statues of sportsman and ballet dancers can be seen today in the public gardens of Moscow and St Petersburg and in the stations of the Moscow Metro.

Yanson-Maniser loved the ballet and sculpted most of the leading dancers of the mid 20th century.

Being a fervent admirer and subtle connoisseur of ballet, Jansen-Manizer suceeded in portraying the individuality of each dancer as well as their grace and athleticism.

Matvey Manizer Soviet Art

As symbols of a specific time and place, they remain a testament to the power of art as a tool of political control.

The state used Manizer’s sculptures as ideological tools.

By placing his works in public spaces, the Soviet government ensured that its citizens would be constantly reminded of the ideals of the revolution.

His sculptures were part of a larger effort to control public perception and enforce the state’s narrative.

-

Soviet sculptor: As a Soviet sculptor, Matvey Manizer was instrumental in defining the visual language of socialist realism. His sculptures were designed to align with Soviet values and propagate the ideals of the state.

-

Matvey Manizer sculptures: Manizer’s sculptures include a range of works from statues of Soviet leaders to depictions of workers and soldiers. These pieces were integral to Soviet public art, used to reinforce state propaganda and celebrate Soviet achievements.

-

Soviet public monuments: Public monuments in the Soviet Union were designed to honor important figures and events while promoting Soviet values. Manizer’s contributions to these monuments helped solidify their role as tools of political and ideological influence.

-

Soviet leaders statues: Statues of Soviet leaders, including figures like Lenin and Stalin, were prominent features in Soviet public spaces. Manizer’s statues of these leaders were designed to be both grand and inspiring, reflecting the central role these figures played in Soviet ideology.

-

Soviet Sculptures: Sculptures created during the Soviet era, reflecting the principles of socialist realism. These works often depicted heroic figures such as workers, soldiers, and leaders, and were used to promote state ideology and commemorate significant events.

-

Propaganda Sculptures: Sculptures designed specifically to convey political messages and promote state ideology. In the context of socialist realism, these sculptures were used to glorify socialist achievements and leaders, serving as tools for ideological education and persuasion.

-

Monumental Sculptures: Large-scale sculptures often erected in public spaces to create a strong visual impact. In socialist realism, monumental sculptures were used to represent the grandeur of socialist achievements and the power of the state, typically depicting heroic and idealized figures.

-

Soviet Public Art: Artworks created for public display in the Soviet Union, including sculptures, murals, and other forms of visual art. These works were intended to be accessible to the general populace and to promote Soviet values and achievements.

-

Socialist Monuments: Monuments created to commemorate important events, figures, or ideals related to socialism and communism. These often included sculptures of revolutionary leaders, workers, and collective achievements, designed to inspire and reinforce state ideology.

-

Soviet-Era Statues: Statues created during the Soviet period, often featuring themes of socialist realism. These statues frequently portrayed key figures in Soviet history and were placed in public spaces to reinforce the state's political messages.

-

Revolutionary Sculptures: Sculptures that depict figures or scenes related to revolutionary struggles and victories. These works often highlight the heroism and sacrifice of individuals involved in revolutionary movements and serve to celebrate and legitimize the revolutionary cause.

-

Worker Statues: Sculptures that portray workers, often idealized to reflect their importance in the socialist state. These statues celebrate the laboring classes and their contributions to the collective success and progress of the socialist society.

-

Collectivist Sculptures: Sculptures that emphasize the collective effort and unity of the working class or society. In socialist realism, collectivist sculptures often depict groups of people working together or engaging in communal activities, underscoring the importance of collective action in socialism.

-

Public Monuments: Large-scale artworks, including sculptures, that are installed in public spaces to commemorate historical events, figures, or ideals. In the context of socialist realism, public monuments were used to convey and reinforce socialist values and achievements to a wide audience.

-

Idealized Figures: Representations of individuals in a manner that highlights their virtues and heroic qualities, often found in socialist realism sculptures. These figures are depicted in a way that emphasizes their importance to socialist ideals and their role in the state's narrative.

-

Monument Preservation: The process of maintaining and restoring monuments, including socialist realism sculptures, to ensure their historical and artistic integrity. Preservation efforts focus on addressing physical deterioration, restoring original appearances, and protecting the cultural significance of these works.

Manizer’s mastery of bronze and marble, combined with his dedication to portraying Soviet ideals, made him one of the most influential artists in Soviet history.

Sculpting History: Matvey Manizer’s Impact on Soviet Art

Matvey Manizer was more than just a sculptor; he was an architect of Soviet identity through art.

His works continue to stand as monumental representations of a political era in which art and propaganda were inseparable.

Understanding Manizer’s contributions is key to comprehending the role of art in Soviet society, and his sculptures remain vital in discussions of how public art can influence national identity.

Matvey Manizer: FAQ

Exclusive USSR Photos

In 1956, Peter Bock-Schroeder (1913-2001) was the first West-Geman photographer to be permitted to work in the USSR.

PBS